Meltwater Champions Chess Tour 2021: Who played the most fighting chess?

Surprisingly, the feedback from my Fighting Chess Index was almost universally positive. I say surprisingly because I thought the final rankings would be controversial, especially Anand’s position (despite the lengthy explanation in the post), and these sort of lists tend to set off angry debates in the chess community. But the debates that were sparked seemed to be around ways to fix ‘the problem’, rather than about the rankings or the statistics. That was personally quite pleasing, because I spent a lot of time trying to keep the FCI objective and addressing all possible objections in the extensive FAQ section.

There were the odd exceptions, but nothing that seriously criticised the methodology. Teimour Radjabov fired off an angry tweet but quickly deleted it, probably because he had not yet read the FAQs and initially assumed the list was some sort of personal attack. The strangest comments were from Hikaru Nakamura, who of course decided to live-stream his reaction. Nakamura agreed with most of the rankings, but when a few positions (Navara and Liem) didn’t match his intuition, he declared that the methodology must be somehow flawed. Despite this, he went on to say that he wouldn’t read the FAQs or the details of the methodology, before claiming that I was accusing norm tournament organisers of rigging events.

On the flip side, many amateurs, organisers and other GMs reached out to me to say they appreciated the list. Most of the GMs were in the 2600-2700 range, which is understandable because these are the professional GMs who typically struggle to receive the big invitations to top events. I even had some correspondence from GMs whose FCI scores were right down the bottom of the list; we broadly agreed that the incentives coming out of the way the professional chess world is currently set up play a large role in “non-fighting” behaviour.

In terms of the technical feedback, there were some interesting discussions, but no concrete problems identified with the index, so I’ve decided to keep it as is. The main suggestions were around ways to incorporate player style and other game characteristics (e.g. sharp positions, frequency of endgames etc.) into the index. However, anything involving the game moves themselves is computationally awkward as well as open to subjective interpretation (which characteristics do you think are the most important?). I like that the current FCI is simple, robust to different specifications and easy to understand, and from the feedback to date, most people seem to agree that it does a pretty decent job.

One thing that I stressed before and want to stress again is that the FCI is not a judgement list. It’s not a ranking of who is ‘good’ and who is ‘bad’. It also doesn’t at all consider a player’s overall performance; whether a player wins all of their decisive games or loses them all makes no difference to their FCI. Similarly, there are plenty of rational reasons for why a player might end up with a low score, and as I wrote in the case of Anand and will also show here below, it can even reflect optimal tournament strategy. How players, spectators and organisers wish to interpret the scores is up to them; all I can say is that the FCI reflects how combative a player is at the board, relative to his or her peers.

***

With that update finished, it’s finally time to move on to the current topic. I received a few emails asking whether I could compute FCIs for the recently completed Meltwater Champions Chess Tour, which was won quite convincingly by Magnus Carlsen. Throughout 2021, social media has seen a fair bit of content around short draws in the events, and particularly the infamous Anti-Berlin Defence repetition. I wanted to see whether the anecdotal comments about certain players were backed up by FCI scores, as well as whether there was any evidence that playing ‘non-fighting’ chess was a good strategy for the Tour.

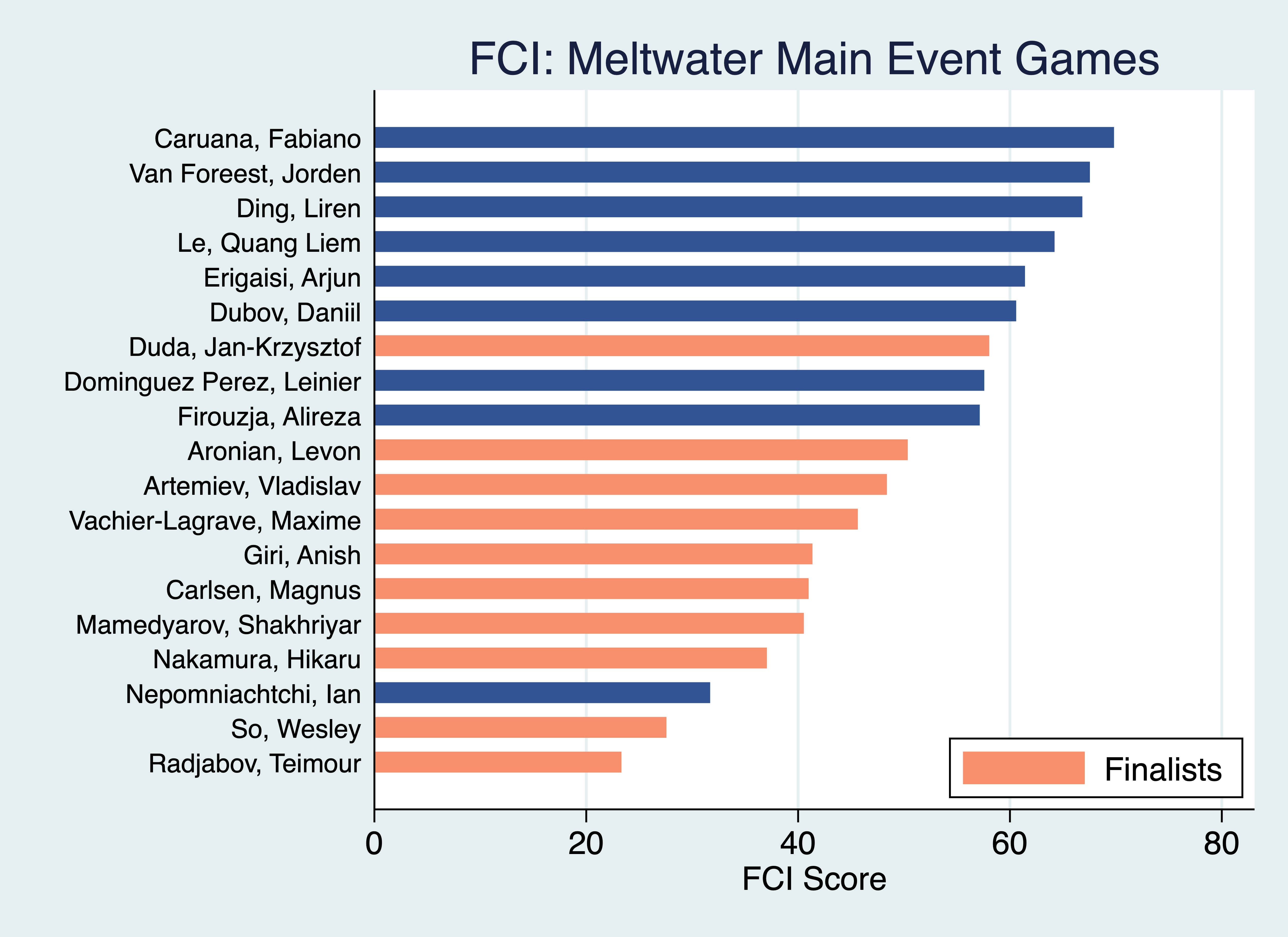

The 10-event series had a fairly complicated structure, with most events consisting of a preliminary tournament followed by a main, knockout event, and a few Armageddon games filtered throughout them. Some players played more events and hence more games than others, some players only played in preliminary events, and the top 10 players contested the recently-completed Tour Final. These differences make the computation of the FCI scores slightly tricky – or, rather, it’s the interpretation that gets tricky. For example, I figured that players in the preliminary events would probably be pushing much harder and longer for decisive results, given the stakes, as well as having played fewer games. So, I started off by just looking at the players and games from the main events and the final.

(Small technical note: The computations follow those of the original FCI, running a principal component analysis over the proportion of draws, short draws, short draws with white and the inverse of the average draw length, and extracting the first component. The FCIs I report in this article have been scaled with a mean of 50 and the identical standard deviation of the original Index, namely, 14.12.)

I’ve highlighted the players who eventually qualified for the Final. That paints a pretty striking picture regarding the hypothesis about optimal tournament strategy: the finalists were generally the players with the lowest FCIs. One could argue that players behaved differently in the Final, but excluding those games makes practically no difference to the rankings (neither does excluding Armageddon games, changing the composition of the Index factors, etc. – I performed plenty of robustness checks at each step).

Just like in the original FCI, Caruana scores highly, as does Liem, while Duda clearly has the highest FCI of the finalists. Caruana’s score is somewhat unreliable as he only played one leg of the Tour (the FTX Cup), and only 10 games in this main event (and extreme FCIs are more likely with smaller game numbers). Despite scoring 7 draws out of 10 games, Caruana had no short draws and an average draw length of 64 moves, which highlights that the FCI punishes short draws and short draws with white much more severely than the overall percentage of draws (and let me stress again that this was not MY decision; the weights are determined by the algorithm).

On the other hand, Duda’s score is calculated across 58 main-event games and is particularly impressive. Despite drawing 25 games, only one of these was within 30 moves: with the black pieces against Magnus in the Final. In fact, the 9 players with the best FCI scores in this group, down to Alireza Firouzja, didn’t play a single short draw with White.

The story at the bottom of the graph closely matches the sentiment spread on my chess Twitter feed throughout the events. I’ll talk more about this after the next graph.

**

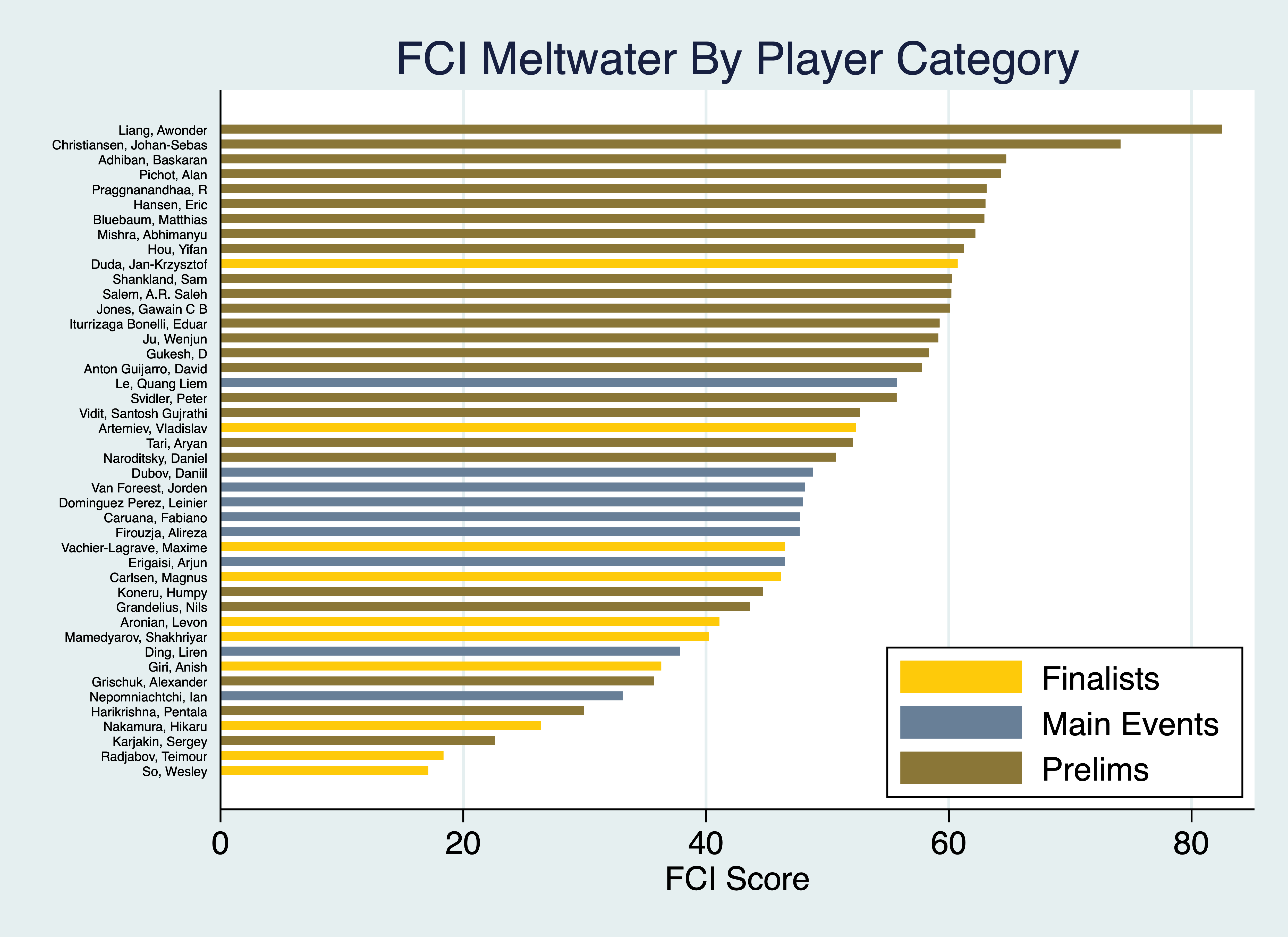

The next thing I wanted to check is: what happens if we include all of the Meltwater games, including the preliminary events? This time, I categorised players by whether they only played preliminary events, played preliminary and main events but not the Final, and of course the finalists. One important caveat is that the only-preliminary players have much fewer games in the sample, so their scores are less reliable. And, as mentioned above, they likely had stronger incentives to play riskier chess – but then again, all the players had the same incentives in the prelims, and the incentives in the main events and the final were also quite strong (certainly at least financially).

The first thing that stands out is Awonder Liang’s massive FCI score, but this and indeed all of the top individual scores (except Duda’s) should be taken with a grain of salt. The sample sizes are too small to conclusively separate these rankings; we can say that all of these players were very fighting, but it’s a stretch to say that one was clearly more fighting than another. For example, both Liang and Christiansen drew exactly three out of 15 games with no short draws, but the algorithm gives Liang the nod solely because of his extremely long average draw length (87 moves!).

However, collectively, each category’s sample is large enough that the pattern of the colours is pretty clear: the players who went deeper into the Tour have lower FCIs.

The second unusual feature is that, for once, Radjabov (FCI: 18.4) is not in last place. That honour goes to Wesley So (FCI: 17.1), who was the runner-up behind Carlsen (FCI: 46.2) for the overall Tour.

What caused these low scores? Wesley drew more than half his games, with the second-lowest average number of moves for his draws (39, behind Karjakin’s 33). For both So and Radjabov, one out of every six games was a short draw, and two-thirds of these short draws were with the white pieces.

**

Finally, I did a quick analysis of the openings that featured in the majority of the short draws throughout the Tour. For the main proponents of short draws, some openings served as a useful energy-saving strategy for two players to make a series of sequential draws against each other in the rapid and/or the early blitz games of the knockouts games. Readers familiar with game theory might see similarities to the Grim Trigger and Tit-for-Tat strategies in a repeated Prisoners’ Dilemma game. The most well-known of these short draw openings, and the most common in the Meltwater Tour by far, is the infamous Anti-Berlin (l’Hermet variation) repetition:

https://youtu.be/wzeNWhq773w

36 games in the Tour featured this exact sequence of moves. 28 of these featured either Wesley So or Hikaru Nakamura (six of these were games against each other). In the table below, and following general wisdom that Black is ‘not to blame’ in these draws, I have ranked the players by how frequently they played one of these openings with the white pieces. But I have also added their Black frequency in parentheses. I created an extra column that pooled together some of the other common (or extremely short) repetitions in the tour: the …Qc3-Qb2-Qc3 Grunfeld, the (admittedly quite pretty) Rg7+ Grunfeld, the dull QGD with Bf4, the Giuoco Piano with Qb3, the ...c6 Anti-Grunfeld, the 6.Be3 Najdorf, and the two games that featured the Bongcloud.

| Player | Anti-Berlin repetitions | Other short repetitions | Total |

| So | 7 (10) | 18 (3) | 25 (13) |

| Radjabov | 1 (2) | 14 (5) | 15 (7) |

| Nakamura | 10 (7) | 2 (9) | 12 (16) |

| Aronian | 3 (2) | 5 (1) | 8 (3) |

| Nepomniachtchi | 4 (0) | 1 (6) | 5 (6) |

| Giri | 1 (1) | 2 (7) | 3 (8) |

| Vachier-Lagrave | 2 (0) | 0 (7) | 2 (7) |

| Mamedyarov | 2 (0) | 0 (4) | 2 (4) |

| Firouzja | 2 (3) | 0 (0) | 2 (3) |

| Ding | 1 (1) | 1 (0) | 2 (1) |

| Karjakin | 1 (4) | 0 (0) | 1 (4) |

| Carlsen | 0 (3) | 1 (0) | 1 (3) |

| Van Foreest | 1 (1) | 0 (1) | 1 (2) |

| Dominguez | 1 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (0) |

| Liem | 0 (0) | 1 (0) | 1 (0) |

| TOTAL | 36 | 45 | 81 |

Combined, Wesley, Radjabov and Nakamura accounted for two-thirds of these textbook repetitions with White. Wesley alone was involved in almost half of these short draws on one side of the board or the other.

But what to conclude? For the fans, the short draws were annoying, no doubt. But the Tour itself was a huge success from all reports, and who knows, perhaps these sorts of controversies actually bring in new viewers. It’s not for me to say, and neither can I blame the players. One thing that is certain: the bottom three Finalists by FCI scores and the most frequent short-draw-repeaters – So, Radjabov and Nakamura – were also three of the highest-earning chess players in 2021.