The Curse of the Chess Book ‘Second Edition’

Do you remember in school or during further studies, the dilemma of deciding which edition of a textbook to buy? As a poor student, I always found it scandalous that the most recent edition carried a hefty price tag that, as far as I could tell, only represented a new cover and a couple of fancy graphics. Now that I’m a lecturer, and when students ask me if they can use an older edition of the textbooks, I almost always say yes. As some point, of course, the updated editions become relevant. But it’s still almost criminal that students are expected to pay for the most recent versions year on year, especially as other products (e.g. software and apps) provide updates for free.

As opposed to textbooks, I love reading chess books. I get such a buzz when a new one arrives in the mail, and usually I devour it, skim-reading the whole thing in a single sitting. Then I’ll go through it slowly over the following weeks, before – if it’s an opening book – finally sitting down with a database and checking the latest theory of its recommendations.

Recently, however, I’ve noticed a bit of a trend towards the ‘second edition’ opening book. Perhaps this is not a trend but just a factor of there being so many books published these days, or perhaps it’s just my own coincidence. Either way, just like my textbooks or even in Hollywood, I’ve found the ‘reboots’ to be generally quite disappointing.

Ironically, a second edition of an opening book usually comes about because the first edition was very well received. The core material of the reboot should thus be high quality. The risk, of course, is that some of it is now outdated, either because of new games or stronger engine analysis than when the book was first published. Consequently, in my opinion there are two bare-minimum requirements for a second edition:

- Theoretically relevant new games should be included, including high-level correspondence games, especially when they refute the recommendations of the first edition.

- The author should check all lines with an engine.

Ideally, the updated edition might also suggest new avenues, tweaking the repertoire to fit modern theory, and might expand the material to include exercises or perhaps strategic explanations in line with current thinking. That’s what I would like to see as a reader. But at the very least, the two points above must be met. If not, I’m buying an expensive copy of the same book, but which is actually WORSE because I now am far more likely to run into a refutation over the board. And that, as all chess players know, is a horrible feeling.

One recent example is “Bologan’s King’s Indian: A Modern Repertoire for Black” (2017). Victor Bologan has made a whole bunch of DVDs and books on the King’s Indian, so he is considered something of an expert. There is quite a lot of overlap in the repertoires between his products, but okay, that’s not a big criticism; authors should write to their strengths, and he knows ‘these’ lines much better than ‘those’ lines, then it makes sense that he focusses on the former.

The 2017 book is a rewrite of his 2009 book “The King’s Indian: A Complete Black Repertoire.” At first, I was puzzled that the rewrite was renamed as well rather than given the ‘Second Edition’ tag, but then I realised there are two different publishers! The 2009 book was (and is) really quite good, with a full, classical repertoire for Black. In his review, GM Glenn Flear, whose reviews are very good, wrote, “Far more than a mere repertoire textbook for club players. An absolute must and a thoroughly enjoyable learning experience.” However, Bologan seems to have milked this project to the max, using largely the same source material for two subsequent DVDs and also the 2017 rewrite. Flear was far less complimentary in his review of the latest book, so much so that the publisher decided to use a quote from his 2009 review in their marketing for the 2017 book!

John Hartmann (reviewer for Chess Life) sum up my thoughts about the “mildly revised” 2017 book when he writes, “readers should pay special critical attention to pages that lack game citations after 2009.” I indeed found a few outdated lines and also omissions in the main chapters, though most of these are unlikely to be exploited below grandmaster level. Most of the recent games are housed in the new chapters, such as the Makagonov systems in the Classical (5.h3). But the extra chapters on the ‘sidelines’ of the London System and Torre Attack are extremely disappointing. Given the huge popularity of the London System these days, especially at club level, I would have expected more than 3 (!) pages out of 400+ pages. A well-prepared London player can easily gain an opening advantage against a KID player who only follows Bologan’s book.

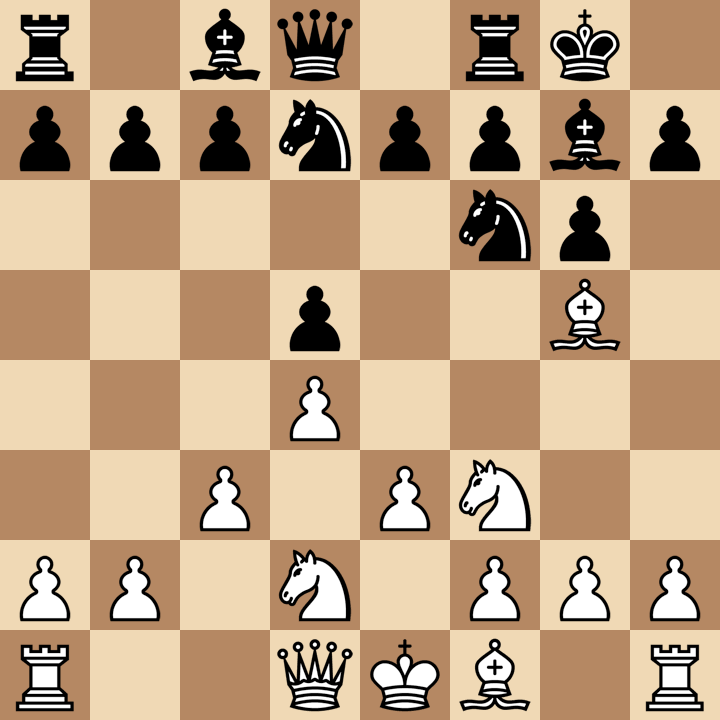

The Torre chapter also is only three pages long, but is arguably more concerning because contains a massive theoretical hole, which, if followed blindly by a reader, leads to a very dangerous pitfall for Black. After 1.d4 Nf6 2.Nf3 g6 3.Bg5 Bg7 4.Nbd2 0-0 5.c3 d5 6.e3 Nbd7,

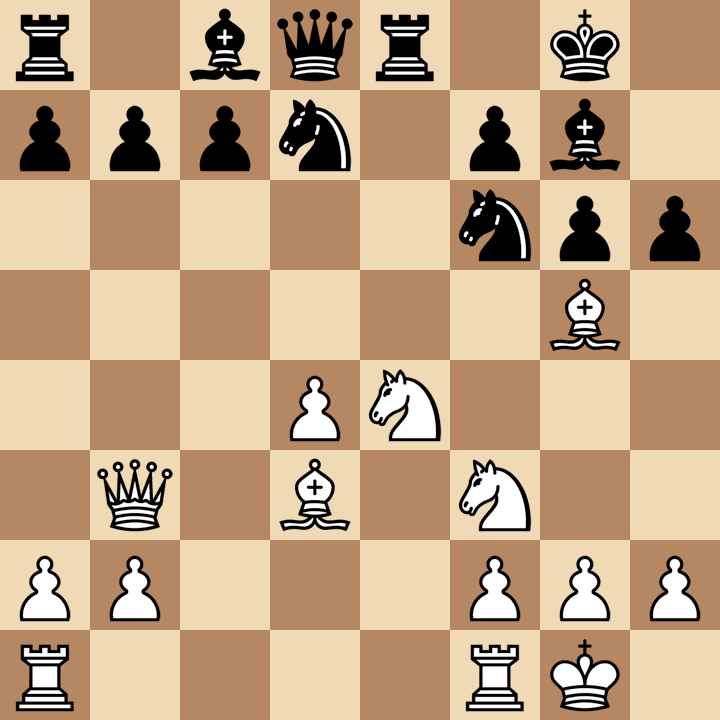

Bologan’s line continues with 7.Be2, with the note “The assessment of the position does not change after 7.Bd3 Re8 8.0-0 e5 9.dxe5 Nxe5”…etc. This is true, and 9.dxe5 indeed used to be the most popular move… before 2009! But since then, 9.e4 has well and truly taken over, largely because the most popular and natural moves by Black lead to a difficult position: 9.e4 exd4 10.cxd4 dxe4 11.Nxe4 h6 12.Qb3!!,

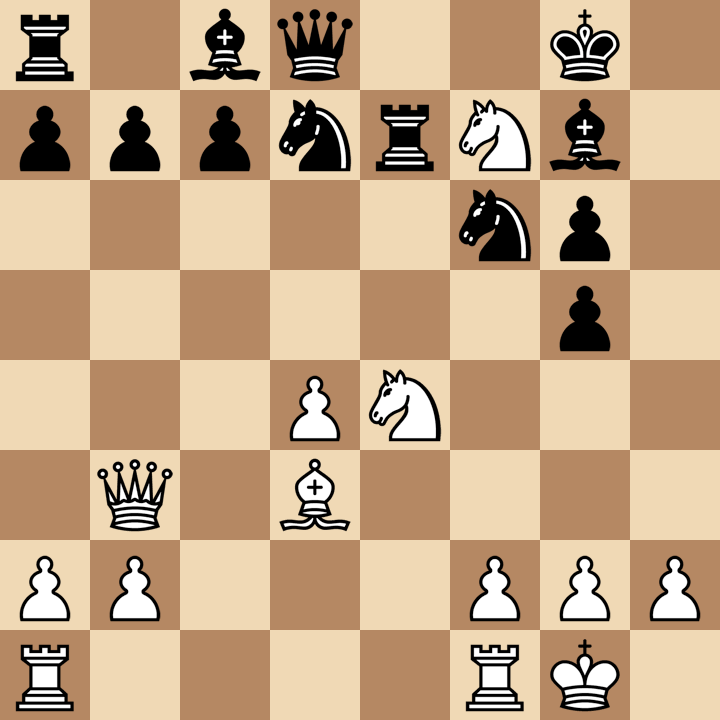

and Black is in trouble. Now 12…hxg5? 13.Nexg5! leads to a winning attack for White, so Black has to find something else. Shirov managed to win after 12…Re7, even though the endgame after 13.Ne5 hxg5 14.Nxf7

14…Nc5!! (the only move; would you find it over the board?) 15.Nxf6+ Bxf6 16.dxc5 Rxf7 17.Bxg6 Qf8 18.f4! favours White. The most popular position in practice has been the awkward-looking 12…Re6, but after 13.Bh4 g5 14.Bxg5! hxg5 15.Nexg5, White is clearly better.

Many opening books have the odd theoretical weakness, of course. Even one of the world’s most diligent authors, Vassilios Kotronias, is not immune. In his outstanding King’s Indian series, Kotronias recommends a line for Black in the popular Mar del Plata variation that leads to a forced loss – though in his defence, the refutation is not supported by engines at first, and neither has it yet been played in an over-the-board game. But several correspondence games prove that White wins by force. There are even two theoretical problems in my own book on the Scandinavian, pointed out by subsequent authors. These things are inevitable (hey, maybe I’ll write a second edition!). But not bothering to check a database or engine, on the other hand, can and should be avoided.

Bologan’s Torre Attack omission is a bad one, especially because it takes only 30 seconds of database research to spot it. If I had white against an opponent who I knew followed Bologan’s book, I would head straight down this variation and pick up my free point. (Incidentally, I mentioned this to a 2700+ GM, who replied that this was typical of Bologan books: “Good ideas, but you have to double-check every line.”) But theoretically speaking, it’s not all bad news for Black. The conservative 10…h6! avoid all of these tricks, but has been rarely played in practice – largely, I suspect, because people don’t expect the 12.Qb3 resource above. Even after 10…h6, though, the structure is quite atypical for the King’s Indian, so as an author, I would want to spend some lines discussing it.

The second ‘second edition’ that didn’t live up to my expectations is Hansen and Heine Nielsen’s “The Sicilian Accelerated Dragon – 20th Anniversary Edition” (2018). This purchase was personally disappointing for two reasons: first, because the original 1998 book is one of the best opening books I’ve read, and second, because I have a lot of respect for Peter Heine Nielsen as a player, a commentator and a person. (I don’t know Carsten Hansen, but a quick search reveals the curious self-applied label “#1 Amazon Bestselling author”.) To be fair, this is a better revamp than the previous one. The authors are upfront that the core material is largely the same, especially when it comes to the explanation of middlegame strategies (which, in my opinion, is what made the original book so great). There is also a brief summary of the recent theoretical developments, which is very helpful, but unfortunately a bit TOO brief. A lot has happened in 20 years! There are 10 bonus annotated games, which again are useful and cover the main theoretical developments – but after 20 years, I would have expected more.

Besides the updated edition being light on updates, there are two other factors that I don’t like. The first is that it seems like a lot of the older material has not been engine-checked, or at least not thoroughly. Quite often I was surprised that the engine’s top choice was not mentioned (for either side). People were barely using engines at all before 1998, and their quality is dwarfed by what you’ll find on today’s smartphone. Normally, the engine-omissions are not theoretically a big deal, as they are often in sidelines and you can easily supplement the book’s material with your own engine-based analysis. Every now and then, however, I noticed an important one.

The second thing I don’t like – and here I am perhaps showing my pedantic side – is finding typos. In the Foreword, Hansen writes that they have tried to remove the typos of the 1998 book – well actually, he tries to write this, but in an ironic twist, puts two typos in that very sentence, including forgetting the word “remove”! And there remain quite a few more throughout the pages of the 2018 edition. Typos happen, of course, but 20 years is a long time to find them…

Overall, however, I would still recommend the book to someone who doesn’t have the first edition. This style of clearly explaining middle game structures and strategies is often forgotten by many modern authors, unfortunately myself included. In fact, this element of both books is so good that, if buying it came with a theoretical/engine-based ‘addendum’, I would still probably rate it five stars. But if, like me, you already have the first edition, then you may feel a little short-changed by the anniversary edition.

Now that I have stopped reviewing chess books ‘professionally’, I feel more freedom to be critical of things I don’t like (not that it really stopped me before). But I do feel a bit guilty in this case, because the original books of Bologan and Hansen/Nielsen are really, really good, especially the latter. Like I said, a second edition usually comes about precisely BECAUSE the first edition is so well received. Perhaps this is why my expectations are so high, and usually unmet, for the sequels.

Still, not all second editions are disappointing. Just like Cooper’s “A Star is Born” and Hendrix’s “All Along the Watchtower”, you do occasionally get a surprisingly good remake that is better than the original. I recently got my hands on “The Modern Tiger” (2014), the cleverly named revamp of GM Tiger Hillarp-Persson’s first book “Tiger’s Modern” (2005). (I actually got the idea of the title of my book from his, but “The Modern Smerdon” doesn’t quite sound as good for a second edition!)

Tiger is an extremely diligent and principled person, and the first book was good, so I wasn’t surprised to find that the 2014 book is excellent. It is completely, and I mean completely, updated. Basically, he has written a completely new book on his opening, and has used his old book as a comparative reference so that he can point out to readers of the original where they should pay attention to update their repertoire. The variations contain reams of updated correspondence and classical games. But he also goes further, analysing novelties for both sides even though these haven’t yet appeared in practice, thoroughly engine-checking everything, and also clearly stating when he disagrees with the engine’s evaluation (and why). It is clear that he has invested a huge amount of time and effort into this second project. Although the Modern doesn’t really appeal to me as an opening, I am seriously considering learning it just because the book is so good. And given that the Modern is a rival to my own Scandinavian, that’s the highest compliment I can give!

Your book is still my favorite chess openings book of all time! Now, 3.5 years after this post, are there any updates on whether/when you plan a second edition? Thanks!

Another recent example is the second edition of Chris Baker’s A Startling Chess Opening Repertoire (first edition published in 1998), which was updated substantially by Graham Burgess. The main selling point is that the lines have been checked freshly with Stockfish and Leela Chess Zero (which are now my two main analysis engines). Having seen a preview of the early chapters at Amazon, it looks a mixed bag to me. Burgess has done a great job in places, notably coming up with novel ways for White to liven up play in the line 1.e4 e5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.Bc4 Nf6 4.d4 exd4 5.0-0 Nxe4, and giving the line 1.e4 e5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.Bc4 Bc5 4.0-0 d6 some good coverage (Chris Baker overlooked 4…d6 completely in the first edition). However, I am not so impressed by the minimal updates to 1.e4 e5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.Bc4 Bc5 4.0-0 Nf6 5.d4 Bxd4 6.Nxd4 Nxd4, where the authors still recommend Koltanowski’s variation 7.f4 d6 8.c3, and the coverage is rather thin, not really addressing the many objections that Lev Gutman raised against the line in his extensive analysis of these lines in Kaissiber 22-24.

Hi David,

I have probably used the Scandinavian as my main defense against 1.e4 for over 40 years, even though I often had to “suffer” in all the 2…Qxd5 lines. I played it against an IM in a simul about three years ago, and he told me that he thought that lines with 2…Nf6 were more playable and might be more fun for me to play. He was correct, and I have enjoyed learning from your book over the last three years. I suggestion I have for your “second edition” should it ever come to fruition, or perhaps a blog post if it doesn’t, is a section in which you give a consolidated overview of what Black should be striving for in each line, e.g., where do Black’s pieces ideally belong, which are the most important squares to control, the key ideas (i.e., the sort of things that some of the authors in the “Starting Out” series often do), etc. Thanks for your consideration, and I hope to use opening tonight at my chess club.

Some books that get past the 2nd edition tend to be quite good, often completely rewritten like Tiger’s approach, e.g. John Watson’s Play the French and perhaps Jeremy Silman’s How to Reassess Your Chess as a non-opening book.

John Shaw found one in his 2016 “Playing 1.e4” book on minor lines (p.334-339). It’s in the line 3.d4 Bg4 4.Bb5+ Nbd7 5.f3 Bf5 6.Nc3. Fortunately, I have found a fix. The other line I would prefer to keep to myself for the moment, because it’s not been published by anyone as far as I can tell, and I’m still playing this opening as black! But I will mention it in any second edition It’s not the Caruana line, however. 9…h5 would have been find for Black in that game, and in any case, I generally prefer the 3…Nbd7 lines.

It’s not the Caruana line, however. 9…h5 would have been find for Black in that game, and in any case, I generally prefer the 3…Nbd7 lines.

Patrik, thanks for your considered comment. And for picking up my typo I believe all authors have an obligation to engine-check their lines using the best available engine at the time of writing, as well as checking all correspondence games played until that point. But of course, engine versions approve, and I wouldn’t hold that against them.

I believe all authors have an obligation to engine-check their lines using the best available engine at the time of writing, as well as checking all correspondence games played until that point. But of course, engine versions approve, and I wouldn’t hold that against them.

In my book, all lines were checked to a minimum depth 28 using the latest Stockfish (at the time, I think it was 8). But for the trickier lines, I also ran Monte Carlo simulations and engine-engine matches after fiddling with the optimism parameters, sometimes for days at a time. And in one case in particular, I’m glad I did!

Perhaps we should start a website to collect these published errors.

Very good reviews! Your review has multiple typos in it by the way, such as “Hartmann sum up my thoughts.” I would add that most Black repertoires published these days are aimed at making you believe a variation is playable and fully sound and intentionally omit problem lines, which are often the whole reason you bought the book.

Is there a single chess repertoire book we can point to that was deeply engine-checked (say, all positions in the book at depth 35 on the latest Stockfish version and checked on Leela)? From seeing all of the new books, my understanding of it is that none of them are even remotely close to that and have minimal explanations of choices or typical advantages to play for, so why would I even buy the books? You might have depth 26 Stockfish 8 analysis in the best opening book we can cite, but at that depth, the evaluations are far less stable. This is why essentially all opening books seem quite low quality. The authors don’t have standards for deep analysis which is needed for serious chess work. It’s all about getting a payday for sub-par work. David has much lower standards than other readers like myself.

I found major errors in the following books: 1. Berg’s Winawer books (his main line against 7. Qg4 loses for Black)

2. Kotronias’s KID books (his Fianchetto KID, 9. Ne1 line, and 9. b4 lines all lose for Black, while he does not equalize in the Saemisch)

3. GM Repertoire 12: The Benoni (White has a major advantage in four of the main lines, seemingly intentionally left out by the author) — and many others. I was really disappointed by this, because I bought these books to battle against the toughest lines with the latest GM preparation, and even the books by Quality Chess were quite low quality and didn’t address my concerns. As always, I have to do the work myself…

Your very topical article put me in mind of the strange case of “The Modernized Reti Opening” by Adrien Demuth. First edition, 439 pages, published Dec 1, 2017. Extended new edition, 447 pages, published January 1, 2019, — while the first edition was still in print. No explanation. No statement about what has been changed or added. No offer of a web-based update for owners of the first edition. May I say that I have considerable reservations about Thinkers Publishing. It seems to be a publishing and distribution service only. In particular, TP does not seem have any editors whose job it would be to catch errors and omissions. No problem: just publish a second edition!

Excellent article. Thanks! I echo Paul’s question. Could you also mention the two lines in your book that now have theoretical problems? Is one of them the line seen in Caruana-Akobian, U.S. Championship 2016? http://www.chessgames.com/perl/chessgame?gid=1819624

Kotronias recommends the …Rf6 system against 13.Rc1. If you have a correspondence database, you need only follow his recommended line together with what has recently played on the ICCF server to see where White takes over. However, even though objectively Black is lost, these positions are still very complicated in practice.

Hi David, I have the Kotronias books. Would you have the reference or moves for the losing line he inadvertently recommends in the MDP variation? Thanks!